Food Sovereignty in the Andes: An Ecofeminist Perspective

Food sovereignty is defined as the right of peoples to define their own agricultural and food policies, prioritizing local and sustainable systems over transnational corporations. The Andean countries are currently facing a food crisis due to the lack of understanding and appreciation of the rediscovered forms of agriculture practiced by local communities and their contributions to economic and social development as providers of environmental services, protecting both landscapes and culture (Romero, 2022).

Andean women are the ones who carry out care work within their communities — they wash and cook with the water from rivers and lagoons that they have or once had access to. Consequently, they have developed their own approaches to ecofeminism and community feminism to respond to the abuses they face regarding access to water (Puleo, 2011). This short article seeks to answer the question: How does ecofeminism contribute to rethinking food sovereignty in the Andes from an environmental and gender justice perspective? It does so through a critical theoretical analysis and bibliographic review.

In Latin America, it is often assumed that women’s struggles are primarily related to other areas not directly connected to ecology. Hence, it becomes relevant to ask: to what extent do feminism and ecology speak to one another as social movements? Beyond having to deal with the glass ceiling or gender-based violence, pollution also aggravates women’s quality of life due to organic characteristics that make them particularly vulnerable. For example, toxic substances tend to accumulate more in women’s bodies.

Therefore, it is crucial that food comes from ecological production. Otherwise, a person may consume up to fifty varieties of pesticides per day: “The Women's Environmental Network, based in London, has drawn attention to institutional passivity in the face of the alarming rise in breast cancer over the past fifty years, mainly due to environmental pollution” (Puleo, 2011). Environmental policies often fail to take gender differences into account—something that must change.

The Western discourse of sustainable development has much to say and teach regarding ecological practices. However, indigenous communities have long held their own ecological visions and conceptions. For instance, the theory of community feminism (which shares the essence of ecofeminism) rescues the experiences of women living in Andean communities in countries like Ecuador, Bolivia, and Peru, and vindicates ancestral knowledge about living in harmony with Mother Nature. It is telling that in texts written by these women, ecology is not mentioned as a novel practice, nor is nature referred to as a resource, because nature is seen as an equal, and ecology is intrinsic to their culture and worldview (Cabnal, 2019).

Despite the fact that Andean countries have recognized nature, water, and the environment as subjects of rights in their constitutions, these are also the very places where communities risk their lives to defend their territories. On multiple occasions, Indigenous and mestiza women have had to appeal to international bodies such as the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) to seek justice for their lands. They have also accused their governments of various abuses. In Ecuador, for instance, when it comes to land concessions for extractive industries—both mining and oil—communities denounce the absence of free, prior, and informed consent as required by law, as well as instances of armed violence by the military or even cyberattacks targeting activists’ emails in search of sensitive information (Toki, 2015).

In the case of oil extraction concessions, several incidents have been documented—such as in Ecuador—where pipelines have ruptured due to poor maintenance or malpractice, causing oil spills that contaminate rivers, seas, lagoons, and vegetation. The extractive companies responsible for mitigating these consequences initially approach affected communities to clean up and provide aid, but their efforts are insufficient and improperly executed. Rivers are never truly cleaned, and in some cases, companies have offered “monthly food packages” to affected families. Yet these families feel insulted, as such aid barely lasts two weeks, does not reach everyone, and includes products they are not accustomed to consuming. These are people who cultivated and ate their own food, raised animals for consumption and sale—animals that now die or become sick due to pollution. This situation clearly demonstrates how extractive industries destroy the food sovereignty of local communities (Basantes, 2020).

Furthermore, these populations suffer from cancer, skin diseases, and stomach ailments, with women being disproportionately affected due to their caregiving responsibilities. They are the ones who must tend to the sick and ensure their families are fed—thus, the loss of food sovereignty and the rise of contamination once again harm women in multiple dimensions.

When industry representatives approach communities to purchase land and the latter resist, they often resort to corrupt and violent practices such as bribery and intimidation—mafia-style tactics. Frequently, with state support, these communities are threatened by military forces. Groups of women from these communities have organized and resisted the sale of their lands, only to face misogynistic psychological pressure from industries that place sexist propaganda in their territories with slogans like: “Who runs your home, you or your wife?”—a deeply patriarchal attempt to pressure men into selling land as a way to prove their masculinity (Baez, 2019). When external patriarchy collides with internal patriarchy within communities, it results in what is known as patriarchal entanglement—a form of double discrimination against Indigenous women.

It is essential to question the limitations of the Western model of food security, which focuses solely on the availability and access to food without considering who produces it and how. Expanding the concept of food sovereignty from these perspectives strengthens resistance against the dispossession of commons such as water, seeds, and landscapes, and opens new possibilities for transformation and epistemic justice (Micarelli, 2018).

Various studies have shown that food diversity contributes to better health by ensuring adequate intake of essential vitamins and nutrients. In contrast, the expansion of the “modern diet” based on processed foods and a handful of crop species has deteriorated public health, resulting in alarming rates of obesity, hypertension, and diabetes—especially in Latin America (Leisa, 2018).

In conclusion, food sovereignty in the Andes cannot be understood without recognizing the fundamental role of women as guardians of life, territory, and ancestral knowledge. They sustain food production through a logic of care, ensuring not only the nutrition of their communities but also the preservation of ecosystems and traditional agricultural practices. Through ecofeminism and community feminism, Andean women have made visible the deep connection between body, land, and food, challenging the patriarchal and extractivist structures that threaten both their autonomy and that of nature. Their struggle for access to water, land, and healthy food is, in essence, a struggle for dignified life and for environmental and gender justice.

Rethinking food sovereignty from an ecofeminist lens means acknowledging that the solutions to the food and ecological crises will not come from industrial models or Western development paradigms, but from local practices centered on reciprocity, solidarity, and care. In the Andes, women are leading alternatives that challenge the agro-extractive model and promote sustainable agroecological systems capable of feeding communities without destroying their territories. Strengthening their voices and participation in decision-making is thus essential to ensuring a real, inclusive, and transformative food sovereignty—one where life, both human and non-human, becomes the axis of collective well-being.

References

Baez, M. (2019). Ternura Michelle Báez Aristizábal profesora Ciencias Humanas. Issuu. https://issuu.com/freddycoello/docs/la_voz_de_octubre/s/11309194

Basantes, A. (2020, July 13). Ecuador: la rotura del oleoducto OCP revela el impacto de construir en zonas de alto riesgo La rotura del OCP en Ecuador: ¿un riesgo mal calculado? Noticias Ambientales. https://es.mongabay.com/2020/05/ecuador-rotura-oleoducto-ocp-petroleo/

Cabnal, L. (2019). Acercamiento a la construcción de la propuesta de pensamiento Epistémico de las mujeres Indígenas Feministas Comunitarias de Abya Yala. https://elizabethruano.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Cabnal-2010-Propuesta-de-Pensamiento-Epistemico-Mujeres-Indigenas.pdf

Gualinga, P. (2014, September 20). Por qué marcho: ¡Necesitamos dejar el petróleo bajo tierra! | Amazon Watch. Amazon Watch. https://amazonwatch.org/es/news/2014/0919-why-i-march-we-need-to-leave-the-oil-in-the-ground

Leisa. (2016). Revista de agroecología edición especial. https://leisa-al.org/web/wp-content/uploads/vol34n2_leisa.pdf

Martinez, E. (2014, September 3). Esperanza Martínez Yánez, La Naturaleza entre la cultura, la biología y el derecho. Instituto de Estudios Ecologistas del Tercer Mundo y Editorial Abya-yala, Quito, Ecuador, 2014, 128 páginas. https://journals.openedition.org/polis/10298?lang=en

Micarelli, G. (2018). Soberanía alimentaria y otras soberanías: el valor de los bienes comunes. Revista Colombiana De Antropología, 54(2), 119–142. https://doi.org/10.22380/2539472x.464

Puleo, A. (2010). ECOFEMINISMO: para otro mundo posible. Catedra. https://aliciapuleo.net/pdf/fragmento_intro_ecofeminismo.pdf

Romero, M. (2022, December 23). Problemas alimentarios y Estado en los Andes. Lecciones de una crisis - Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar. Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar. https://www.uasb.edu.ec/publicacion/problemas-alimentarios-y-estado-en-los-andes-lecciones-de-una-crisis/

Toki, K. (2017, October 5). Defensoras de los Derechos Humanos y el Medio Ambiente de los Pueblos Indígenas: Comentario sobre la Reciente Audiencia en la CIDH | EarthRights International. EarthRights International. https://earthrights.org/blog/defensoras-de-los-derechos-humanos-y-el-medio-ambiente-de-los-pueblos-indigenas-comentario-sobre-la-reciente-audiencia-en-la-cidh/

Southern Cone, Water Risk: Rural Municipalities v/s Avocado Monoculture farms, Chile

Introduction: The Southern Cone is facing a historic drought driven by both climatic and anthropogenic factors, including deforestation, intensive livestock farming, and monocultures, which have disrupted the hydrological cycle, reduced rainfall, and overexploited aquifers. In Chile, this crisis is exemplified by the Municipality of Cabildo (Petorca), where over 47% of the rural population lacks access to safe drinking water. The expansion of avocado monoculture, fueled by global demand, has intensified water scarcity, soil degradation, and environmental pollution, highlighting the absence of sustainable water management and the increasing ecological vulnerability of the Petorca Valley.

Development: The Province of Petorca (Valparaíso, Chile), characterised by its mountainous geography and semi-arid climate, is experiencing a severe water crisis caused by a combination of prolonged droughts, aquifer overexploitation, and agro-industrial expansion. The La Ligua River, the region’s main water source, has been heavily exploited by agriculture and mining, reducing the availability of water for local communities. The native xerophytic vegetation has been largely replaced by avocado monoculture, which in Cabildo occupies more than half of the agricultural land. This shift has led to soil erosion, pollution, and environmental imbalance, illustrating the conflict between economic production and ecological sustainability in the Petorca Valley.

Results: To estimate the water consumption of an avocado monoculture in the Municipality of Cabildo, data from the company Cabilfrut S.A. were analysed. According to a report by Agraria.pe (26 December 2024), the company exports 8 million kilograms of Hass avocados annually. This figure, excluding potential losses or domestic consumption, serves as the basis for calculating water use per mature tree. Three scenarios —conservative, moderate, and high— are proposed to estimate the total water consumption associated with this annual production.

8 million kg of avocados per year / 12 months = 667 kg of avocados per month.

The production of Hass avocados in Chile varies according to the age of the trees, irrigation management, and planting density. In Petorca, intensive orchards predominate due to their high water demand and the pursuit of production efficiency.

|

Plantation´s type |

Trees per hectare (density) |

Average production trees/year |

|

Traditional (5m x 5m) |

400 - 500 |

40 – 60 Kg |

|

Intensive (3m x 3m or less) |

800 - 1000 |

25 – 40 Kg |

A tree in an intensive plantation produces an average of 35 kilograms of avocados per year.

Trees numbers = (8.000.000 Kg/year) / (35 Kg/tree/year) = 228.571 trees

Therefore, the company Cabilfrut S.A. would require approximately 228,571 mature trees to achieve an annual production of 8 million kilograms of avocados.

Representation of three cases: Considering a density of 800 trees per hectare, a 30-day month, and a total of 228,571 trees, it is possible to estimate the evapotranspiration-based consumption.

|

Cases |

Characteristics |

Litres/trees/day |

Tree consumption per month (litres) |

Total tree consumption (m3/month) |

|

conservative |

Less demanding climate or highly controlled irrigation |

30 |

900 |

205.714 |

|

moderate |

Intermediate value for Hass in semi-arid zone |

60 |

1800 |

411.428 |

|

high |

Typical intensive plantation |

100 |

3000 |

685.713 |

Considering irrigation efficiency allows for the estimation of the actual volume of water extracted from wells or aquifers. In drip irrigation systems with 70% efficiency, part of the resource is lost through evaporation, whereas with efficiencies of 50–60%, water demand increases significantly, exacerbating the pressure on water resources.

E.g.: moderate case, extraction required = 411,428 (m³/month) / 0.70 = 587,754 (m³/month)

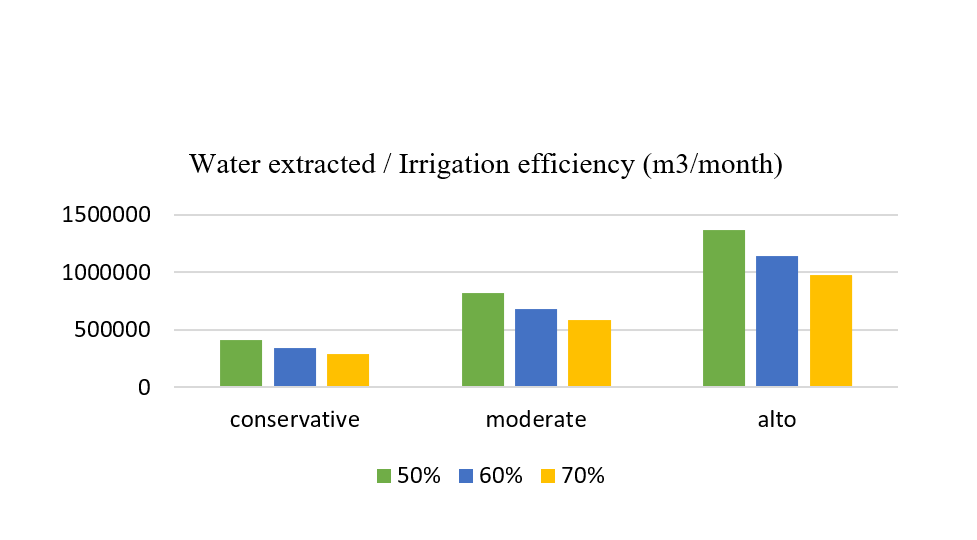

The bar chart compares the monthly water consumption (m³) of mature avocado trees in three scenarios, according to irrigation efficiency. With greater efficiency (close to 100%), losses and consumption decrease; with lower efficiency, these increase significantly.

Conclusion: The estimated water consumption values vary according to the season, soil type, tree age, and irrigation efficiency. Using meteorological data, it would be possible to determine the average consumption during summer and winter and develop new scenarios.

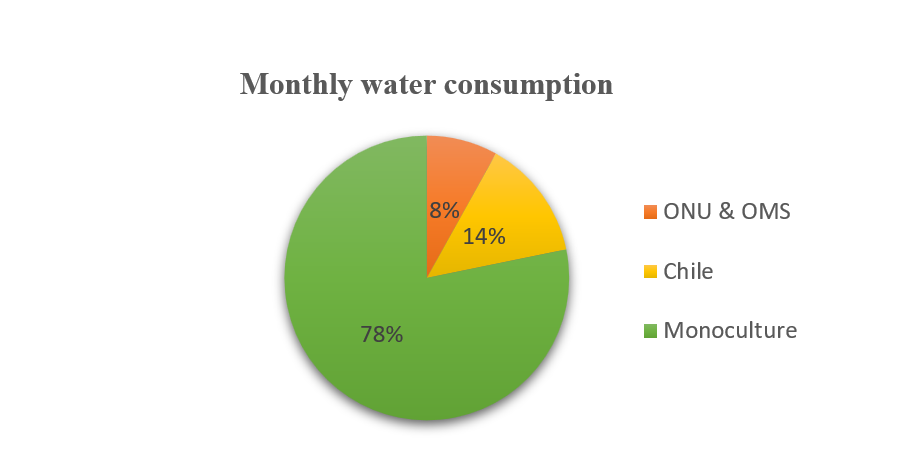

According to the United Nations and the World Health Organization, an individual requires 100 litres of water per day to meet basic needs. With a population of 20,215 inhabitants (Cabildo, 2024), the estimated consumption is 60,645 m³ per month, while considering the national average of 170 litres per day, the value would rise to 103,097 m³ per month; however, this figure remains constrained by local water scarcity.

The pie chart illustrates the significant disparity between the monthly water consumption of avocado monoculture and that of the population in the Municipality of Cabildo, where agricultural demand far exceeds domestic use. In addition to water scarcity, the area faces aquifer contamination from fertilisers, air pollution from pesticides, and soil erosion. The valley’s enclosed geography intensifies heat and traps particles, creating a local greenhouse effect. Agricultural expansion has replaced native vegetation, disrupting biodiversity and ecological cycles, thereby contravening SDG 6 of the United Nations 2030 Agenda, which advocates for equitable access to clean water and its sustainable management

References

Ministerio del Medio Ambiente de Chile. (2023). Informe Nacional de Escasez Hídrica

Dirección General de Aguas (DGA). (2022). Diagnóstico de la Cuenca del Río Petorca

INDH. (2019). Informe sobre Derechos Humanos y Agua en Chile

Valdés-Pineda, R. et al. (2021). 'Water governance and avocado production in Petorca Valley, Chile'. Water Policy Journal

Ley 1122/1981. Código de Aguas, República de Chile

Text: William Rebolledo, Melany Chango